Well, hello there. My name is Dan, and welcome to the right side of my brain. As you may be aware, the right side of the brain is the artistic and creative side. So this is where all thoughts on the media I consume goes, a creative mixing pot of all my thoughts and observations on the art I love so much.

Who asked you, Einstein? Let’s get a second opinion. From my own personal scientist.

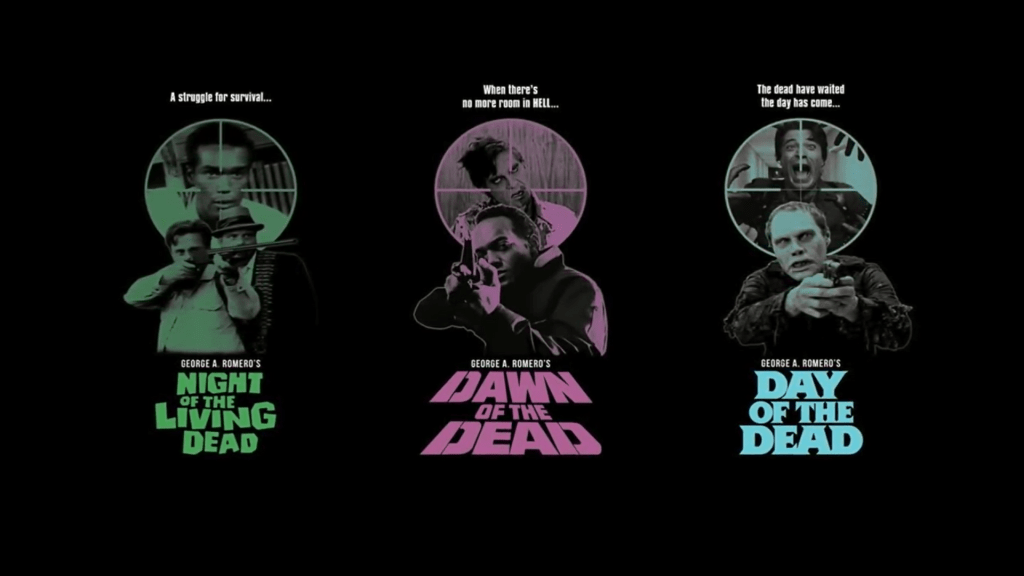

Alright, in actuality this is just a weaksauce gimmick for my blog that I will probably regret in a year. Moving right along, I wanted to start with something pretty simple. Let’s start with a super original observation; George A. Romero’s Dead Trilogy (Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead) are a trio of films that use socially conscious observational storytelling to brilliantly convey a three-act apocalypse. Yup, this is the kind of unique insight you can expect on this blog. Okay, so clearly this is an observation that has been made a thousand times, but only because it is not just true, but also wholly distinct even in the oversaturated zombie genre that these movies spawned. In fact, George Romero’s storytelling was so brilliant that the three-act apocalypse doesn’t just occur over three whole movies, but within the opening scenes alone. All three of these movies have some of the most effective openings I have ever seen, and the point of this article will be to explore why they are so brilliant, and how they single-handedly depict the three-act apocalypse. So, without further nonsense:

Night of the Living Dead’s opening is mundane, but thick with an atmosphere of dread. We open on siblings Barbara and Johnny visiting their father’s grave. The scene plays out slowly, with a lot of casual dialogue. The setting immediately gives off the sensation of death, which the characters naturally catching on to. Johnny teases Barbara about her childhood fear of the graveyard, eventually catching on to the fact that she is still afraid of it. This prompts him to tease her with the instantly iconic “they’re coming to get you, Barbara,” pointing out a shambling old man and teasing that he is a risen corpse before playfully running away. As Barbara walks after him the old man makes his way over to her and suddenly attacks her, and in that instant the horror begins. Johnny returns to fight off the zombie but dies in the skirmish, Barbara runs and drives for her life as the creature unrelentingly chases her in a long sequence that eventually leads her to the house where the rest of the film takes place.

As I pointed out in the summery, the most effective thing about this scene is how suddenly the apocalypse begins. Compare this to other zombie media like 28 Days Later, The Walking Dead, or even the remake of Dawn of the Dead. All of these products create a step by step descent from normalcy into hell. In Night of the Living Dead, we go from the mundane to a waking nightmare in an instant. In the greater scheme of the rest of the trilogy, we have witnessed the exact second the world began to end. This is it, no lead in, no explanation (I mean, the film does mention something about radiation from Venus, but that’s dumb and other movies disregard it). This quick descent is also effective for the scene itself, as the genuine shock and terror does a lot to mask a potentially silly chase, one which popularizes the trope of the running woman constantly falling down so as not to easily outrun her shambling pursuer. This is the most impressive thing about Night of the Living Dead in general, how the effective use of pacing and mood manages to lift up what could be an otherwise very hokey low budget horror flick.

Dawn of the Dead is very clever in how it captures the state of the entire world in a relatively confined space. We open in a news station where two of our main characters, Fran and Stephen, work. This scene handily establishes two important facts about the state of a world that is now some time into the zombie apocalypse. One is that in spite of the now uncontrolled outbreak society is still trying to hold together, and two is that it is badly failing. The studio is in total chaos. Everyone is arguing, no one is holding the place together, and we see all the “experts” being interviewed making it increasingly clear that no one has any answers about what is going on or how to handle it. The scene ends with Fran and Stephen abandoning ship in the stations helicopter. They eventually meet with SWAT team members Peter and Roger, who themselves have abandoned a housing project raid that went terribly wrong, with dead bodies the tenants refused to hand over coming to life and attacking them, and stressed SWAT members opening fire on living and living dead alike.

While Night of the Living Dead highlighted how individual people cannot cooperate even under the direst of circumstances, Dawn of the Dead turns its critical eye to human society as a whole. While this movie’s individuals do mostly fine on their own, we regularly get to witness the greater humanity seemingly going insane around them. Talk shows and interviews are full of bickering and conflicting statements, and our character’s morale is slowly drained as it becomes slowly clear that there is no hope of civilization holding together in this crisis. We see cops still committing racially motivated murders even in a project full of zombies and biker gangs still rebelliously destroying sanctuaries and attacking people with no real cause. While the Dead Trilogy is fundamentally about the dead overtaking the living, all three movies—but Dawn of the Dead especially—puts the true onus on the living for their own demise.

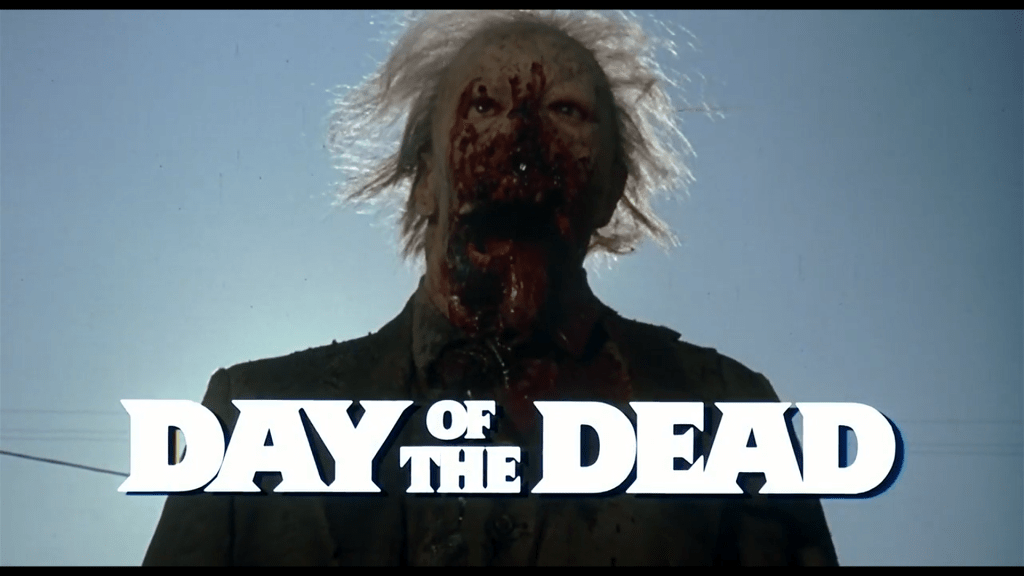

Day of the Dead, while generally considered a lesser film than its predecessors, has the most chilling opening of them all. Our leads, part of a group of scientists and soldiers holed up in a secure bunker to find a solution to the outbreak, go to a nearby town to search for survivors. As their calls echo through the town we are treated to a montage of total desolation. It’s the little things that really inform the world building of this scene. There is loads of money being blown along with the trash through the wind, visually equating the two. There is a newspaper with the headline THE DEAD WALK, indicating that it has not been too long since the outbreak began. An alligator on the steps of town hall are the only signs of life…until we see a lone figure walking the streets, then revealed as the handsome boy pictured above. More zombies begin to emerge from the surrounding buildings, the previously empty streets quickly becoming a sea of the living dead, and the protagonists dejectedly return to their sanctuary, having clearly been through this song and dance countless times in countless towns.

Day of the Dead is easily the grimmest of the trilogy, almost entirely based on this opening. The characters in this film are trying to find a solution to the zombie problem, but from the word go we see that there may be no humanity to meaningfully save anymore, a fact later confirmed when the head scientist calculates that the zombies outnumber humanity 400,000 to 1 at this point. On top of that we have the usual George Romero status quo where the remnants of humanity still can’t coexist, even in the most desperate possible circumstances, as the soldiers and scientists are constantly at each other’s throats over the lack of progress being made, basically all except the leads having been driven insane by cabin fever and stress by this point. We see that humanity could not change its ways no matter what, and ultimately the only solution offered by the film is for the few sane people left to just leave it all behind and take the opportunity to start over.

So, I have established why these openings set the tone and show the step-by-step downfall of humanity on their own and how that informs the films both individually and as a whole. But why does this matter? Well, I think what makes this so impressive is that for as perfect as it is, it is also not by design. All three of these movies were made almost a decade apart. They are essentially George Romeo making individual film essays about the way human civilization was declining in the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s respectively, all incidentally tied together by the ongoing zombie apocalypse, which he probably only returned to for the sake of keeping people watching. Yet the trilogy fits together more cohesively then some of the planned franchises I have seen.

I have written this trying to find an answer to what makes this work so well, but the only answer I can find is that George Romero was an obscenely talented artist who knew how to make potentially rote social commentary both interesting and entertaining, and who had a special talent for starting a story. It’s not much, but it’s always worthwhile to appreciate great artists where you can find them, so I guess if you or I can take anything from this unremarkable little write-up it’s that George Romero was great and will be missed. And that’s all I’ve got for today. Any input from the scientific end?

I thought you weren’t real.

…See you next time.

Very enlightening and entertaining.

LikeLike

Fantastic !! Actually kept me reading.

LikeLike